In a previous post I briefly described the Olmec culture and placed it into context alongside other cultures of Mesoamerica. The Olmec culture played a large role in the Preclassic Period, although it was not the only culture present in Mesoamerica then. In today’s post we will go over what we know of Olmec culture, mostly through its art.

Olmec Culture: What do we know?

Not much is actually known about the people who left us the beautiful, monumental art of the Olmec. However, what we can put together from archaeological context tells us that the Olmec thrived in the Gulf Coast area of Mexico from around 1800 BC to sometime around 400 BC. Although Michael Coe has suggested in his book “Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs” that the Olmec might have been a Mayan-speaking group that expanded from the Gulf of Mexico to the eastern Yucatan Peninsula, confirmation has not yet been found.

Important Olmec sites include San Lorenzo, La Venta, El Manati, Tres Zapotes, and Laguna de los Cerros. At these sites we find evidence of a strong and powerful civilization that had access to stone drainage, long-distance trade and large-scale architecture. The leaders of these sites were powerful enough to commission monumental works of art made from stone found hundreds of kilometers away, and, typical of the Preclassic, we see class distinctions begin to appear. At San Lorenzo, for example, archaeologists have uncovered evidence that the city center, placed on a hilltop, was the home to many elite residences, while lower-class residences would have been built down below on the plain.

What are the characteristics of Olmec art?

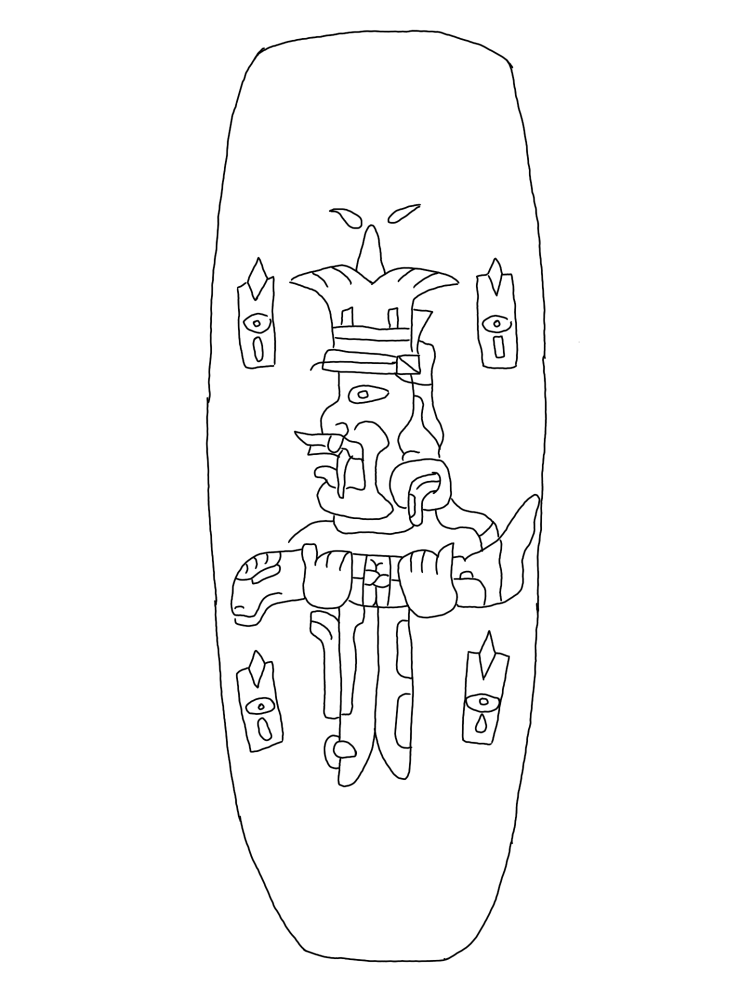

Evidence of the Olmec artistic style has been found throughout the rest of Mesoamerica, including Central Mexico and the Pacific Coast of Mexico and Guatemala. Perhaps the most well-known examples of this art are the colossal heads found at different sites. The monumentality and volume of these objects display many of the characteristics of Olmec art: bold, broad lines that create volume and a full, round shape; round curves instead of sharp geometric angles, and a lack of excessive detail, which adds to the monumental feel of even the smallest pieces.

Olmec art shows humans, deities and transformations between the two. Although scholars used to think that these transformations represented a race of humanoid creatures descending from a woman who copulated with a jaguar, this theory has been debunked. Now these transformation figures are seen as religious or political leaders who shift from human to animal form, and vice versa. They are characterized by a cleft head, symbolizing corn emerging from the earth, and down-curling lips sometimes accented by large fangs.

What do we learn from Olmec art?

Although we might not know as much about the Olmec from archaeological context as we know about later groups, the art left behind does tell a lot about this culture. For example, we know that the concept of human-animal transformation was widely known and represented, and must have been important at least to community leaders.

Second, the art has given various representations of deities belonging to the Olmec culture. These deities are frequently associated with elements of nature, such as rain or lightning or corn, and were likely invoked in order to ensure a plentiful harvest.

Finally, the sheer monumentality of Olmec art, and its ubiquitous nature throughout Mesoamerica, testifies to the complex society that created these works of art. These are not the creations of small villages, but of thriving, complex societies with social stratification and abundance. Through the monumental art left behind, we can overcome the lack of other data and get a glimpse into the Olmec world.